In about a week, my youngest child will be two months old. She is sleeping right here in her crib beside me. When I look at my two daughters, I often think to myself, "I'm a father?!? I'm their father! I sure hope I turn out to be a good one." It's sort of like learning to ride a bike. At a certain point, the training wheels come off and you hope you don't crash.

You probably draw most from your own father in going about your fatherly duties. For instance, after hearing the word "butt" and the term "shut-up" from my eldest child in the back seat on our ride home from art camp this past week, I told her, "that's not nice and we don't say that because it's ugly." Undeterred, she let it rip again. This was the exchange:

Bethany: Can I say butt?

Me: No. That's ugly.

Bethany: But you said but.

Me: There's a difference. Don't say butt again. It's not nice.

Bethany: What if I say it like "buuuttttt I'm thirsty."

Me: If I hear you say butt or any variation thereof again, we're going to pull off in the ditch and I'm going to spank your fanny good.

Bethany: Well, can I say fanny?

Me: No.

Bethany: Well you said fanny so why can't I say fanny?

Where did that exchange come from I thought in retrospect? The answer: from my own childhood. I'll be the first to tell you that for every good spanking I did get, which were relatively few, I deserved tenfold more. But I did come to respect the authority of the leather belt. And Daddy had a vintage one from the 1970's that had to be about two inches wide. It commanded my utmost respect.

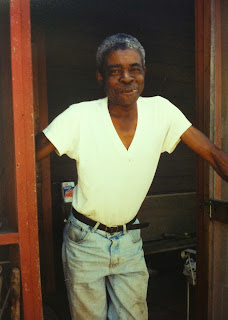

One time, I intentionally and with much premeditation punctured my sister's front bicycle tire as repercussion for using my "boys only" bicycle ramp. But I made the rookie mistake of leaving the tools I used in the crime at the scene. Rather than confess, I went on the run. As in, running across our yard towards the woods in hopes I'd be able to climb a tree like a renegade cougar and wait out the pursuers until nightfall when they'd give up and go inside. No such luck. My father is 6 foot 5 inches tall and caught me in about two steps. Despite my demands to be extradited into the custody of my grandparents, I received a sound and well deserved spanking.

Like most anyone, my life was shaped by my parents. I'm thankful they were both there and cared about me. I'm thankful that they taught me right from wrong and that disregard came with consequences. Though I fall short daily, they taught me to take the high road and turn the other cheek. Only when you become a parent can you know how lucky you were as a child to have parents that loved you and taught you these things.

It is an absolute fact that no family is perfect. Like every person, every family has its flaws. But just to have a family is a special thing in life. To have a father that saw you as his child and not an expense or obligation seems to be a fleeting commodity these days. I wrote this because my 3 year old daughter walked out on the back porch tonight and said to me, "Daddy, what are you and me going to do tomorrow?" My answer: fishing. And we're going. Creek fishing with cane poles and crickets.